“CBDCs might replace commercial banking. Having the government rather than commercial banks is more efficient, less costly and allows more people to be included in that system” – Dr. Diego C. Nocetti, Dean, School of Business, Southern New Hampshire University (SNHU)

Imagine a world where paper money is obsolete, and every transaction from buying food to paying your mortgage is done with government-backed digital currency. This is not science fiction; it is quickly becoming reality. In countries like China and the Bahamas, central banks have already launched digital currencies, setting the stage for a global financial revolution. But as more nations explore these Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs), questions about privacy, security, and the future of traditional or private banking loom large. Before diving into the specifics of CBDCs, let us give an overview of the scope of this topic. While the topic of CBDCs seems to be a very modern affair, the first example of it was seen in 1993 by the bank of Finland. While this would end up failing some years later, this got the ball rolling for other central banks to start developing their own iterations of CBDCs. Today over 100 central banks have their own CBDC, are in the process of one, or have determined that a CBDC is not the right fit for their country. While the story is different for every country, this has implications for many private sector digital currencies and traditional banking institutions, and how they will coexist or be replaced in the future.

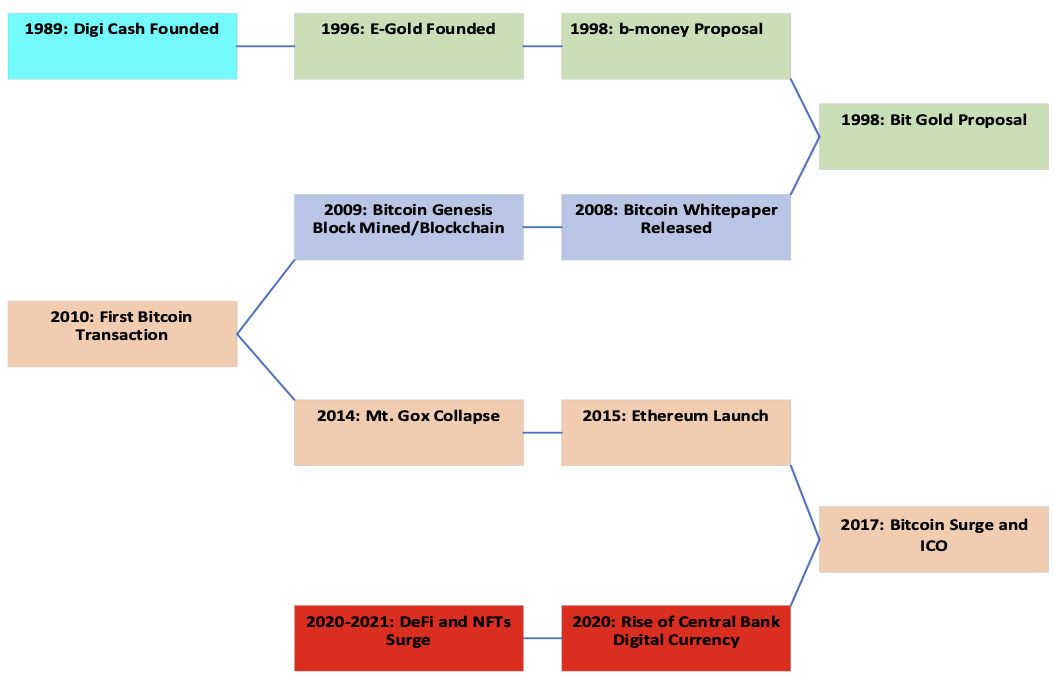

THE EVOLUTION OF DIGITAL CURRENCIES

Did you ever wonder how digital currencies grew to the point where they became part of everyday conversation? From news headlines about Bitcoin’s volatility to governments considering their own CBDC, the world of digital currency became a significant topic of interest. Yet, the path to this point was much more complex and dated back several decades, starting with early ideas about digitizing money and evolving into the creation of cryptocurrencies that dominated the financial discussion. Below we show a “roadmap” of digital currency development.

Early Concepts of Digital Money (1980s-1990s)

The concept of digital money existed as early as the 1980s when advancements in technology led people to consider how traditional forms of cash could be translated into a digital format. This was a time of growing interest in privacy and anonymity, driven by the increasing digitalization of personal data. Cryptographers like David Chaum saw this moment as an opportunity to explore how electronic payments could be secure and anonymous, paving the way for digital cash systems. In 1983, Chaum introduced the idea of “blind signatures” in his paper, “Blind Signatures for Untraceable Payments”, which laid the foundation for Digi Cash, one of the first serious attempts at creating a digital currency. Chaum’s vision was to protect user privacy while still allowing secure transactions; a challenge that would resonate through the evolution of digital currencies.

Founded in 1989, Digi Cash offered anonymous transactions, a revolutionary idea at the time. However, despite its innovation, Digi Cash went bankrupt in 1998, as they struggled to gain traction due to a lack of widespread internet use and limited adoption by financial institutions. Its fall was an early indication that the world might not yet be ready for fully digital currencies, even though the underlying ideas such as cryptography and privacy would later become critical to the success of future digital assets.

Around the same time, another initiative known as E-Gold, founded in 1996 by Douglas Jackson and Barry Downy, gained popularity. Backed by gold reserves, this new initiative allowed users to make online payments, providing a digital alternative to physical money. Despite its initial success, E-Gold faced legal challenges, particularly surrounding its use in money laundering activities, and was eventually shut down in 2009. The rise and fall of E-Gold underscored both the potential and pitfalls of early digital currencies, highlighting issues of regulatory compliance that future innovations would need to navigate. These challenges, however, did not stop the quest for a decentralized form of digital currency, one that would not rely on any single authority.

Development of Cryptographic Currencies (1990s-2008)

By the late 1990s, cryptographers and innovators experimented with the idea of decentralized, cryptographically secure digital currencies. Wei Dai’s B-money proposal in 1998 outlined a system where transactions could be conducted without a central authority, using anonymous accounts and distributed consensus to maintain a ledger. Though B-money was never implemented, it introduced the core principles of decentralization and privacy that later became crucial to the rise of cryptocurrencies. Similarly, Nick Szabo’s Bit Gold, another precursor to Bitcoin, proposed a system where proof-of-work would be used to secure digital transactions without a central party overseeing the network. Bit Gold, while never fully realized, would later be recognized as a critical steppingstone toward the development of the first successful cryptocurrency.

These early theoretical frameworks would soon evolve into practical applications, laying the groundwork for what would become the largest cryptocurrency we have today, Bitcoin. Szabo’s concept of proof-of-work would later be a critical component in ensuring the security and integrity of decentralized networks, making it possible for Bitcoin to operate without the need for central authority.

The Birth of Bitcoin (2008-2009)

The turning point for digital currencies came in 2008 when an anonymous figure or group under the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto released the whitepaper, “Bitcoin: A Peer-to Peer Electronic Cash System”. The paper outlined a revolutionary concept: a decentralized digital currency that used blockchain technology and proof-of-work to validate transactions. By removing the need for a central authority, Bitcoin introduced a new model for financial transactions. In January 2009, Nakamoto mined the first block of the Bitcoin blockchain, the so-called “genesis block”, marking the official launch of Bitcoin.

Bitcoin’s reliance on blockchain technology, a distributed ledger maintained by a decentralized network of nodes, ensured transparency and security in a way that had not been achieved by earlier digital currencies. As a result, Bitcoin became the first truly decentralized cryptocurrency, and its success opened the door for an entire ecosystem of digital currencies that would follow. The ideas pioneered by Bitcoin, such as the use of cryptographic proof to prevent double spending, became foundational components of later cryptocurrencies, further solidifying its role as the cornerstone of the digital currency revolution.

Early Adoption and Growth of Bitcoin (2009-2013)

Bitcoin’s journey took a significant turn in 2010, when the first recorded commercial transaction occurred. A programmer named Laszlo Hanyecz famously paid 10,000 BTC for two pizzas, an event now celebrated as Bitcoin Pizza Day, symbolizing the currency’s initial foray into real world commerce. As Bitcoin gained traction, the establishment of the first Bitcoin exchange, Mt. Gox, in 2010 provided a platform for users to trade Bitcoin for fiat currency, significantly enhancing its viability and accessibility. However, the collapse of Mt. Gox in 2014, following a major hacking incident that resulted in a loss of over 850,000 BTC, underscored the vulnerability in the nascent cryptocurrency market.

In the aftermath of the Mt. Gox incident, Jon Matonis, the executive director of the Bitcoin foundation, emphasized that while Bitcoin was still in an experiential phase, it has shown remarkable resilience. He wanted investors to “only invest in what you can afford to lose,” underscoring the inherent risks in a rapidly evolving financial landscape. Matonis also expressed optimism, predicting that Bitcoin would move into the mainstream within 3 to 5 years, driven by the development of user-friendly applications that would facilitate broader adoption (CNN Business, 2014).

Emergence of Altcoins and Blockchain Innovations (2011-2015)

The period from 2011 to 2015 saw the emergence of alternative cryptocurrencies, or “altcoins”, designed to improve upon or offer different features compared to Bitcoin. One of the earliest and most notable altcoins was Litecoin, created by Charlie Lee in 2011. With faster transaction time and a different hashing algorithm called Scrypt, Litecoin aimed to address some of Bitcoin’s limitations while expanding the cryptocurrency ecosystem.

In 2015, the launch of Ethereum by Vitalik Buterin introduced a groundbreaking concept in the realm of digital currencies, smart contracts. These self-executing contracts allowed for the automation of agreements without the need for intermediaries, thereby opening the door for decentralized applications (d-Apps) and decentralized finance (DeFi) systems. Ethereum’s versatility marked a significant evolution in blockchain technology, expanding the use cases beyond mere currency and into a platform for innovation and development.

The introduction of Ripple (XRP) in 2012 further diversified the cryptocurrency landscape, focusing on facilitating cross border payments and working within the traditional financial system. Unlike Bitcoin’s decentralized approach, Ripple was designed to provide rapid, low-cost international transactions, gaining traction among banks and financial institutions as a viable alternative to existing payment systems.

Initial Coin Offerings (ICO) and Their Impact (2017)

By 2017, the cryptocurrency market exploded into public consciousness, thanks in large part to Bitcoin’s dramatic price increase. Starting the year around $1,000, Bitcoins’ value surged to $20,000 by December, drawing both institutional investors and individual traders. This bull run marked a pivotal moment, with cryptocurrencies transitioning from a niche interest to a mainstream financial phenomenon. The rapid rise in value, combined with increasing media attention, brought cryptocurrencies into the global spotlight, prompting discussions about regulation, adoption, and future applications.

At the same time, 2017 saw the rise of Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs), a new way for blockchain startups to raise capital by issuing their own cryptocurrencies or tokens. ICOs provided a decentralized fundraising mechanism that bypassed traditional venture capital and allowed for quicker and more democratic funding processes. An example of a successful ICO is Ethereum, which raised $18.4 million in its 2014 ICO, laying the foundation for what would become one of the most influential blockchain platforms in the world. However, not all ICOs were as successful or transparent. Many faced regulatory challenges, and some were outright frauds, leading to increased scrutiny from government agencies like the SEC. Despite the risks, ICOs helped demonstrate the potential for blockchain technology to disrupt traditional finance models, showing how decentralized platforms could democratize access to capital in ways previously unseen.

Regulatory Scrutiny and Institutional Involvement (2018-2020)

As cryptocurrencies’ popularity grew, governments and regulatory bodies started to scan the industry. Many countries introduced regulations to curb the potential for bad practices such as money laundering, tax evasion, of fraud. For example, back in 2018, the U.S. Securities and exchange Commission (SEC) started targeting Initial Coin Offerings that were considered unregistered securities offerings. There were similar regulatory initiatives observed globally, for example Japan and south Korea established frameworks to oversee exchanges and protect investors.

To address the volatility of cryptocurrencies, the stablecoins surged which unlike other cryptocurrencies are pegged to stable assets like commodities. Some examples of stablecoins are Tether (USDT) and USD Coin (USDC), which became popular in this field, providing a bridge between cryptocurrencies and traditional financial systems. The rise of stablecoins came up in regulatory discussions because of their impact on monetary policies and financial stability (Liao & Carmichael, 2022).

By 2020, some major financial institutions like PayPal, Square, and Fidelity started to offer cryptocurrency services, giving as a consequence, more legitimacy to digital currencies in the eyes of the public and institutional investors. This institutional adoption marked a turning point for blockchain technology because of the recognition of the potential benefits of cryptocurrencies by financial institutions. Moreover, the clarity in the regulations helped facilitate this trend, allowing institutions to navigate the difficulties of the crypto market more effectively (Coinmonks, 2023).

The Rise of Central Bank Digital Currencies (2020)

Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) were digital forms of money created by central banks whose primary goal was to modernize the financial system, making transactions faster and more efficient. Unlike cryptocurrencies, CBDCs were backed by the government and were more stable and trusted (Kapron, 2024). Although CBDCs ballooned in 2020 and sounded like a new concept, they dated back decades. The first CBDC was born in 1993 when the bank of Finland launched the Avant smart card, an electronic type of cash but this CBDC eventually dropped in the 2000s (Stanley, 2022). In 2020, the rise of CBDCs occurred because several countries began launching their own CBDCs.

In 2020, China launched the Digital Yuan, becoming the first biggest economy to manage a CBDC. The Bank of China want to improve efficiency in payments and reduce dependence on third-party services such as Alipay or We Chat Pay. In this way China does not only modernize payments but also gave the government more control over the financial system. Another example to be aware of is in the Bahamas with the introduction of the Sand Dollar, also in 2020. Its purpose was to improve financial inclusion, making sure that more people had access to banking services, especially in remote areas. Furthermore, many other countries including those in Europe, the US and Japan were exploring and developing their own CBDCs.

Decentralized Finance (DeFi) and NFTs (2020-2021)

Between 2020 and 2021, a movement called Decentralized Finance (DeFi) surged in popularity. The DeFi platforms allowed users to borrow, lend, trade, and earn interest on cryptocurrencies without the need for traditional banks as intermediaries. These new platforms provide people with more autonomy over their finances when a time of uncertainty economically is happening as it was with the COVID-19 global crisis. Some examples of DeFi platforms are Uniswap and Aave. However, DeFi is not a space free of risk, various issues like fraud, volatility, and lack of regulation are some problems that have affected this field, leading to discussions about the need for better supervision.

By 2021, Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) also exploded into the scene. An NFT is a unique digital asset that means ownership of a digital and physical item as if could be a piece of art or a song. That is why so many artists, musicians, and celebrities began using NFTs, consequently creating a new market that captivated a big audience and promoted the versatility of blockchain technology. NFTs had a bigger interest than cryptocurrencies, showing how digital assets can transform creative industries (Anderson, 2021).

Environmental and Energy Concerns (2021-Present)

Since 2021, as the popularity of cryptocurrencies grew, the concerns about their impact on the environment did too. At the time, it was known that cryptocurrency mining involved solving complex mathematical problems that consume big amounts of energy which leads to significant carbon emissions. For example, Bitcoin had an annual electricity consumption of more than 198 terawatt-hours which means almost 95 million tons of CO2 per year which represents a large amount of pollution that countries like Nigeria produce. In past years, many reports have been highlighting the environmental impact on this process leading to many questions about sustainability in this field (Iberdrola, n.d.).

In response, many projects started to focus on more energy-efficient alternatives to be more sustainable. Cardano, Chia, Nano, Stellar Lumens, and Algorand are cryptocurrencies that use proof-of-stake mechanisms, which consume less energy than traditional proof-of-work systems. This change towards greener cryptocurrencies reflects a growth in the awareness of environmental issues within the blockchain community and emphasizes the importance of these kinds of practices (United Nations University, 2023).

Current Trend and Future Directions

During this time, governments worldwide debated how to regulate the quick growth of the cryptocurrency market. Countries such as the U.S., China, India, and the EU have introduced some regulatory frameworks to protect consumers while other countries have taken a more hand-off approach to promote innovation. El Salvador made history in 2021 by adopting Bitcoin as legal tender, an important decision that reflects a shift toward embracing cryptocurrencies on a national level. At the same time, there are more financial institutions and corporations that are integrating cryptocurrencies into their business models. Companies such as Tesla MicroStrategy have made some significant investments in cryptocurrencies, showing a growth in the acceptance of digital currencies in the mainstream financial world. The future direction of cryptocurrencies points to the following: regulatory discussions about coherent frameworks. This also includes licensing for exchanges and consumer protection laws, improvements in sustainable practices, and introducing educational initiatives to promote responsible investment and financial literacy (Comply Advantage, 2018).

CENTRAL BANKS MOVEMENT TOWARDS DIGITAL CURRIENCIES

Central Banks are a country’s national banking system. They influence a nation’s economy from a macroeconomic perspective by regulating inflation and stabilizing prices. From the microeconomic point of view, the central bank functions as a lender of last resort. Typically, business or individuals would turn to commercial banks, savings and loan companies, credit unions or other financial sources to secure funds. There are several reasons why Central Banks got involved with digital currencies (Sinha, 2022):

-

Financial inclusion: To provide more payment options and ensure resilience and security of central bank money.

-

Efficient monetary policy tools: To reduce or prevent the adoption of privately issued currencies.

-

Competing payment options: To offer consumers and businesses a greater choice of payment options.

-

Declining cash usage: As cash usage declines, central banks are exploring digital alternatives.

As noted above, there are two central banks that have delved into the world of digital currencies, but many more are on the horizon. Central Banks used a procedure to establish a digital currency. This entailed: (1) Central Banks issue CBDCs as a digital form of money, (2) they control the issuance and control of CBDCs, and (3) CBDCs are used to modernize financial systems and improve transactions. In Figure 2, we see a listing of countries and where they are in the CBDC process (Board of Governors-Federal Reserve System, 2023).

One hundred and thirty-four central banks are currently involved in the process of developing their own CBDCs (Atlantic Council GeoEconomics Center, 2024), so what are they and why are central banks rushing to adopt them? These digital currencies are meant to offer a government backed substitute for decentralized cryptocurrencies. They are issued and controlled by central banks to represent a 1/1value of the country’s physical currency. CBDCs allow central banks to maintain greater control over the monetary system, including more efficient tracking of money supply and combating illicit transactions. In many countries, this is allowing underrepresented people and communities to participate in modern online banking, allowing them to be more competitive in the international market. With the international market in mind, CBCDs could revolutionize how countries trade with one another using more compatible currencies that are easier to move and track. Next, we examine the central banks that were early adopters.

But before delving into that information, the authors wondered, “Would CBDCs lead to inflation or more stability”:

“I think it depends on how it is managed; you are making it easier for the government to create money and some of them would use that to try and stimulate the economy and eventually if there is too much money in the economy, it could lead to higher prices. On the other hand, well-managed, I think it can lead to greater financial stability compared to the current system, which is partially managed by the government” – Dr. Diego C. Nocetti (SNHU)

Launched CBCDs

The first adopter of a CBDC was the Central Bank of the Bahamas with their Sand Dollar. The main goals they were looking to accomplish by utilizing digital currency included: increased payment efficiency, greater financial inclusion, and to safely combat illicit and illegal payments. In 2019 the pilot phase of the Sand Dollar program was introduced to the Exuma of the Bahamas. Exuma is an array of remote islands to the south of the main island making it an ideal testing ground for the CBDC (Sand Dollar, n.d.). Over this testing period, over two thirds of the Exumian population would adopt the digital currency as banks were far and few between. They utilized it for salary payments, paying bills and other personal transactions. A year later on October 20, 2020, the Sand Dollar CBDC was moved from the pilot to production phase, rolling out digital currency across the entire country.

Within two years, the Bahamian Sand Dollar had $303,785 in circulation with 33,000 wallets in use. While these number do not seem extraordinarily high, it is important to note that with a population of 415,00 people currently 12.5 percent of the population have an active Ewallet which allows the usage of the Sand Dollar. This percentage is rising as well especially among the population of Bahamians who were previously underrepresented in banking at a rate of adoption around 8% (Wright et al., 2022). It will be interesting to see how in the coming years the Sand Dollar CBDC will continue to grow and blaze the trail for other up and coming CBDCs from central banks in other similar countries.

In the Caribbean, two other key digital currencies have been launched: JAM-DEX in Jamaica and DCash in the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union (ECCU). Both aim to provide secure payment options and reach unbanked populations, helping to improve financial access in the region. This essay looks at their key features, successes, public reception, and challenges. The first digital currency designed for a currency union is called DCash. It offers a quick and affordable method of handling money, which is especially advantageous to unbanked individuals and small businesses. The final ECCU member which accepted it was Anguilla. Despite the excitement around DCash, the area is still concentrating on cybersecurity and digital growth to safeguard users. JAM-DEX, overseen by the Bank of Jamaica, is equal in value to the Jamaican dollar. It serves the 17% of Jamaicans without bank accounts and can be used without Wi-Fi, making it accessible even in areas with poor internet. People can easily open digital wallets with little information, and money can be added via cash, transfers, or ATMs, expanding their reach.

Both currencies have experienced prosperity. ECCU countries like Dominica and Montserrat are seeing an increase in the use of DCash, which facilitates access to financial services for unbanked people and small enterprises. The use of the JAM-DEX has grown in Jamaica thanks to government incentives and its safe, cost-free transactions, particularity among individuals who did not previously use banks. Most users opinions have been favorable. Eastern Caribbean businesses value DCash’s simplicity and security. JAM-DEX has gained popularity in Jamaica as a result of government promotion, especially among individuals who are not familiar with digital banking. The JAM-DEX was officially launched in 2022 after a five-month pilot, trying to get citizens used to this currency. However, its rollout has faced several challenges, particularly in terms of adoption by both merchants and consumers.

Despite initial efforts, like the Government of Jamaica giving $2,500 worth of JAM-DEX to the first 100,000 user, adoption has been slow (Ledger Insights, 2023). By early 2024, only around 20,000 wallets had been registered, for Jamaica’s 2.8 million population, meaning only 9.2% of Jamaicans own a wallet (Rose, 2024). One key issue is the limited readiness of the point-of-sale (PoS) infrastructure. The central bank is now investing in upgrading 10,000 PoS machines to support JAM-DEX, as older equipment needs to be replaced. This equipment limitation has hindered merchant adoption, with only the National Commercial Bank currently providing a fully functional JAM-DEX wallet. The Jamaican government has attempted to boost usage by exploring partnerships with private sector players and encouraging banks to integrate CBDC solutions. Nonetheless, the CBDC is not yet widely accepted, with plan for further infrastructure improvements and wallet development still in progress.

However, both currencies have difficulties. Although efforts are being made to address these concerns some small firms are taking their time implementing DCash, and there are worries over cybersecurity. Furthermore, DCash requires an ID in addition to a smartphone, which may prevent certain people from using it. The primary obstacle to JAM-DEX’s widespread adoption is the death of cellphones and digital literacy in some regions. With this said, DCash and Jam-DEX are significantly enhancing financial accessibility throughout the Caribbean. They provide low-cost, safe payment options while also assisting the unbanked population. These virtual currencies have the power to completely change how people manage money in the area, even though they still must overcome obstacles like security issues and computer literacy.

With these points in mind regarding central banks that have founded and launched CBDCs, we can see there are many positives and many challenges they are facing. Taking a look next at central banks who have CBDCs in the pilots phase we can get an idea of the next evolution of digital currencies being used in our world. A pilot phase is a small-scale implication to see if a project or in this case digital currency is going to be viable. From our research, many of these central banks that are working on a currency in the pilot phase are much larger international players. Countries such as China, Russia, and Brazil to name three. This will switch our focus from better accessibility to banking to larger international transactions between these massive economies.

Pilot Phase CBDCs

Taking a look at China’s central bank first, the digital yuan has been in a pilot phase since 2019, during which it has been assessed in select cities and regions across China. Since 2022, the Chinese government has expanded the distribution of this digital currency, introducing it in new areas and sectors across the country to encourage broader adoption. Initiatives like lotteries and New Year celebrations have been used to promote its use. The e-CNY has been assessed in major cities such as Zhenzhen, Suzhou, Chengdu, Xiongan, Shanghai, Beijing, and the Hainan province, as well as cities like Changsha, Xi’an, Qingdao, and Dalian. By the end of 2022, there were 260 million individual wallets registered, representing 18.57% of China’s total population (Sharma, 2024). However, despite the government’ efforts, many Chinese citizens continue to prefer alternative payment methods like WeChat Pay and Alipay.

Concerns about the People’s Bank of Chaina (PBOC) potentially using the digital yuan to monitor transactions have caused hesitation, even though the PBOC claims that small-value transactions remain completely anonymous. By 2019, 86% of China’s population was already using mobile payments, a well-established habit that makes it challenging for the digital yuan to gain widespread traction. To further encourage its use, the Chinese government has partnered with private companies such as Tencent and Alibaba, the parent companies of WeChat Pay and Alipay, to integrate e-CNY into these popular payment platforms (Sharma, 2024). China’s adoption of a digital currency could have significant global implications, as its position as the world’s second largest economy may encourage other countries to follow its lead. Another key factor is the Belt and Road Initiative, a large-scale infrastructure and economic development project launched in 2013 to boost trade and investment across Asia, Europe, Oceania, Latin America, and Africa. Through this initiative, Chian could leverage its digital currency to strengthen international economic ties and expand its influence in global finance.

As noted, China has emerged as a leader in the digital currency landscape, with its digital yuan undergoing extensive testing across the country. However, it was Sweden that pioneered the early development of central bank digital currencies with the e-Krona, placing itself among the first nations to explore and innovate in this field. The e-krona is still in its pilot phase, with the Riksbank beginning research into Sweden’s central bank digital currency as early as 2017. Several pilot programs have been conducted since then, and by 2024, the central bank had expanded trials to include simulations of payments, user interactions, and integration with commercial banks (Sweden’s Riksbank, 2024).

To promote future adoption, the Riksbank has partnered with commercial banks and fintech companies to ensure that the e-krona will be integrated into existing payment systems. The bank is also focused on making the e-krona a resilient option, ensuring it works offline to provide security in the case network outages (Anderson, 2024). Sweden is already one of the most cashless societies in the world, so the e-krona is designed to complement the existing digital payment methods and provide a publicly backed alternative in case of disruptions to private payment providers. This initiative could encourage other countries to follow suit, integrating CBDCs into their established payment systems as a secure option alongside private solutions. However, there are concerns about how the e-krona will interact with privacy and financial stability. Many Swedes already use services like Swish, so questions remain about how much additional benefit the e-krona will provide. Furthermore, as with other CBDCs, concerns around government surveillance of transactions exist, though the Riksbank is working to ensure that privacy is maintained.

With China and Sweden’s pilot phase CBDC in mind, we transition to central banks that are currently researching or in the development phase. These phases are crucial in laying down the framework the digital currency will be built upon. It will be important to see what steps these central banks are taking given the accomplishment of other CBDCs and to also learn from their failures. The model used from (Tourpe et al., 2023) represents the steps the CBDC management teams are going through in developing a CBDC that is suited to work in the United States. It starts with the policy management team identifying parts needing work from the development team based on results from the previous go/no-go evaluation. By getting the results and communicating back with the policy management team, the go/ no-go decision can be made. This allows the transitions of CBDCs through the phases we have discussed throughout the paper thus far.

Research Phase CBDCs

The Digital Dollar is currently in its research phase, with discussions about its potential beginning. To explore the potential of a digital currency, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston has partnered with MIT on a project known as Project Hamilton. Project Hamilton focuses on building and testing proprietary technology of a potential digital dollar. From the Phase 2 planning, it is evident they are looking to build the most advanced CBDC to date likely to entice the hesitant US population (Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 2022). In 2022, the Federal Reserve also released a discussion paper to gather feedback on how a CBDC could function in the US, focusing on its potential benefits for financial inclusion and modernizing the payment system.

In terms of adoption strategy, the US government is gathering data and feedback, with no clear timeline for a formal launch. However, there has been increasing focus on partnering with the private sector, including banks and fintech firms, to ensure that any future digital dollar would integrate smoothly into the existing financial system. Public sentiment towards a digital Dollar is currently unfavorable , with a recent survey indicating that only 16% of Americans support the government issuing a central bank digital currency. Among the respondents, there are significant partisan differences: 24 % of Democrats support a CBDC, while only 7% of Republicans feel the same way (Elkins & Gygi, 2023). Many Americans express concerns about privacy and the potential for government surveillance of individual transactions, especially since a digital currency would be centralized. Additionally, people are already accustomed to using private digital payment platforms like Venmo and PayPal.

The global implications of a digital Dollar would be significant, as it could strengthen the US Dollar’s dominance in international markets and global finance. It might accelerate the adoption of central bank digital currencies worldwide, prompting other nations to follow suit. A digital Dollar could also enhance the speed and efficiency of cross-border transactions, reducing costs and dependence on intermediaries like SWIFT. However, it could also raise concerns about monetary policy control in countries heavily reliant on the US dollar, potentially shifting the global balance of financial power.

As we have seen, Central Bank Digital Currencies are rapidly gaining attention, with most countries around the world now developing their own digital currencies. This global trend demonstrates the potential for CBDCs to transform the financial system, while improving financial inclusion and offering central banks greater control over monetary policy. Despite this momentum, public sentiment towards CBDCs remains skeptical, particularly regarding concerns over privacy, security, and government surveillance. Privacy will be a critical challenge that will need to be addressed, as maintaining a balance between user privacy and the need for transparency will be crucial.

“CBDCs present various advantages, including their secure nature due to central bank backing, which instills trust in digital money. However, they come with disadvantages such as potential privacy concerns due to transaction tracking, as well as risks related to cybersecurity” – Dr. David Moreno Casas, Professor, Universidad Camillo Jose Cela

As more countries continue to explore and implement CBDCs, it will be interesting to observe how these issues are tackled in the coming years. Technology has the potential to revolutionize global finance, but how it evolves will depend on how these concerns are managed and how CBDCs are integrated into the financial system.

OPPOSITION TO DIGITAL CURRENCY

In the last decade, digital currencies, particularly cryptocurrencies and Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs), gained significant attention. Proponents hailed their potential for revolutionizing global finance, improving transaction efficiency, and expanding financial inclusion. However, digital currencies had not been universally embraced, and many influential groups had expressed concerns about their impact on financial markets, regulatory frameworks, privacy, and broader socio-economic issues. In this section of the article, we examine the key stakeholders opposed to digital currency adoption and the rationale behind their resistance.

A Threat to Financial Stability and Monetary Policy

Central banks and governments were the most prominent and vocal opponents of widespread digital currency adoption. While central banks had recognized the potential benefits of CBDCs – such as faster payments, increased transparency, and reduced reliance on physical cash – they were hesitant to embrace them due to concerns about financial stability and the erosion of monetary policy tools. One significant concern was the potential disintermediation of the banking system. If individuals and businesses were to shift their savings into CBDCs, it could reduce the amount of funds held in commercial banks, which in turn would limit banks’ ability to provide loans and credit. This could undermine the traditional role of banks in the economy, leading to liquidity shortages and more volatile financial markets.

Furthermore, central banks relied on tools like interest rates and open market operations to regulate the economy, control inflation, and manage crises. The introduction of a CBDC could complicate these efforts by changing the dynamics of money supply and demand. For example, if people held more money in digital form, central banks might struggle to influence economic behavior in the same way they did with physical cash or deposits in commercial banks. Additionally, governments and financial authorities were wary of digital currencies being used for illicit activities, including money laundering, tax evasion, and terrorist financing. Digital currencies, especially decentralized ones like Bitcoin, could facilitate anonymous transactions that were difficult to trace. Although CBDCs would offer more control than cryptocurrencies, governments still worried about the potential for misuse, especially if robust regulatory measures were not in place (Bank for International Settlements (BIS), 2024).

Regulatory Bodies and Law Enforcement

Regulatory bodies shared similar concerns regarding the risks to consumers and investors in an unregulated digital currency landscape. As the World Economic Forum (2023) highlighted, the volatility of cryptocurrencies, coupled with the lack of standardized regulations, could lead to significant financial losses for investors. Regulatory bodies feared that digital currencies could lead to market instability without adequate oversight, particularly as their speculative nature attracted retail investors who might not fully understand the risks involved.

Law enforcement agencies, including the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), faced increasing challenges in combating digital currency related crimes. Scams, fraud, and ransomware attacks that demanded cryptocurrency payments were on the rise. Criminals exploited digital currencies’ pseudonymity and cross-border nature to conduct illicit activities while evading detection. This had prompted law enforcement to call for better tracking tools and stricter regulations to limit the use of digital currencies in illegal schemes (US Department of Justice, 2022).

However, the decentralized nature of many cryptocurrencies made it challenging to implement effective regulatory or enforcement measures. Even with CBDCs, where governments could maintain control over the issuance and tracking of currency, there were concerns that what the infrastructure needed to monitor and prevent illegal activities could be resource-intensive and technologically challenging to establish (World Economic Forum, 2023).

Privacy Advocates: Concerns About Government Surveillance and Personal Freedom

Privacy advocates were deeply concerned about the potential for digital cryptocurrencies, particularly CBDCs, to be used as tools for government surveillance. Unlike cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, which could offer a degree of anonymity, CBDCs would be subject to complete oversight by central authorities. This could allow governments to track every transaction, potentially infringing on individuals’ financial privacy and freedoms (Hinchliffe, 2024).

In the context of CBDCs, governments would have unprecedented access to citizens’ financial activities, enabling them to monitor spending patterns, enforce taxes, or even control how and where digital money was used. Such concerns had prompted debates about the potential misuse of personal data, with privacy advocates warning that this could lead to authoritarian surveillance regimes where personal financial autonomy was severely curtailed.

Moreover, in countries with weak data protection laws or governments with a track record of infringing on civil liberties, CBDCs could be weaponized to punish political dissidents, restrict freedom of expression, or enforce social control. The very infrastructure that could make CBDCs secure and efficient might also be used to erode personal freedoms if not designed with stringent privacy safeguards in place (International Monetary Fund, 2024).

The Environmental Cost of Cryptocurrency Mining

Environmental groups like the Sierra Club strongly opposed digital currencies due to their substantial environmental impact, especially the mining process associated with cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin. The method known as Proof of Work (PoW), used by many cryptos, required miners to solve complex mathematical puzzles, necessitating vast computational power and consequently, significant energy consumption.

Bitcoin mining consumes as much energy annually as some small nations. Most mining operations were concentrated in regions where electricity was generated from non-renewable sources like coal or natural gas, exacerbating carbon emissions and contributing to climate change. Environmental advocates argued that the proliferation of cryptocurrencies without proper regulation or a transition to more sustainable technologies, such as Proof of Stake (PoS), could negate efforts to combat global warming. The environmental cost of cryptocurrency mining also concerned the governing body of the Sustainable Development Goals. Mining operations often occurred in areas with cheap energy, sometimes leading to the displacement of communities and local environmental degradation. Advocacy groups argued about implementing stricter regulations and developing greener alternatives that could balance the benefits of digital currencies with the urgent need to address climate change (DeRoche et al., 2022).

Social Justice and Inequality: Exacerbating the Wealth Gap

Social justice advocates and inequality activists worried that digital currencies could exacerbate existing economic inequalities. While proponents argued that digital currencies could promote financial inclusion by providing access to the unbanked, critics pointed out that these technologies were often inaccessible to the very population they were intended to help. For instance, Oxfam America had raised concerns that they poor and unbanked populations in developing countries often lacked the technological infrastructure (e.g., smartphones, reliable internet access) or the financial literacy necessary to use digital currencies effectively. As a result, digital currencies might only benefit wealthier individuals who already have access to these resources, leaving marginalized groups further behind (Kayastha et al., 2022).

Additionally, the speculative nature of cryptocurrencies had led to concerns about economic exploitation. In some developing countries, workers had been paid in volatile digital currencies, which could lose value quickly, leaving them financially vulnerable. Moreover, in countries where labor practices were weak, cryptocurrencies could be used to circumvent legal wage protections, making it harder for workers to secure fair compensation (Rosales et al., 2023)

A Threat to Established Business Models

Legacy financial institutions, including traditional banks and payment providers, viewed digital currencies as a significant threat to their business models. Cryptocurrencies and CBDCs have the potential to disrupt the traditional financial ecosystem by enabling peer-to-peer transactions without intermediaries. This disintermediation could lead to a loss of market share for banks and payment providers like Visa and Mastercard, who had built their businesses on processing transactions and lending money.

These companies were lobbying heavily for regulations that would show the adoption of digital currencies and protect their existing business models. Their primary concern was that digital currencies could undermine their role as trusted intermediaries in the financial system, particularly if widely adopted. Moreover, banks could face a liquidity crisis if customers moved large portions of their deposits into digital wallets, reducing the capital available for lending and investment.

Legacy financial institutions were also concerned about the potential disruption of payment systems. Digital currencies, especially stablecoins and CBDCs, offered the potential for faster and cheaper cross-border payments, which could make existing international payment systems obsolete. This directly threatened traditional remittance services and foreign exchange markets, where fees and transaction times were significantly higher (Reynolds, 2020).

Volatility, Security, and Regulatory Uncertainty

Technology skeptics raised concerns about the inherent volatility of cryptocurrencies and the security risks they posed. Unlike traditional currencies backed by governments that tend to remain stable, cryptocurrencies could experience massive price swings in short periods. For instance, Bitcoin’s price had fluctuated dramatically, sometime losing over 50% of its value in just a few months, which made it a hazardous investment.

Security was another major issue. Cryptocurrencies and digital wallets were frequently targeted by hackers, resulting in the theft of billions of dollars’ worth of assets over the years. The decentralized mature of many cryptocurrencies meant that, unlike traditional bank accounts, there was often no recourse for victims of theft or fraud. Additionally, the lack of robust regulatory framework in many countries left investors and businesses uncertain about the legal status of their digital assets, further increasing the risk.

Technology skeptics also highlighted the regulatory uncertainty surrounding digital currencies. While some governments had taken steps to regulate cryptocurrencies, the legal landscape remained fragmented and constantly evolving. This created challenges for businesses and investors trying to navigate a market where the rules might change anytime (Sun, 2022).

THE IMPACT OF DIGITAL CURRENCIES ON GLOBAL TRADE

The advancement of digital currencies pushed us into a new era of global commerce, changing how trade had been conducted and reshaping the financial landscape. Digital currencies such as Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) aimed to revolutionize trade, with promises of reducing costs, increasing transaction speeds, and fostering financial inclusion. As businesses and governments explored the potential of the ideas, the rapid expansion also brought challenges, including regulatory concerns, cybersecurity risks, and geopolitical implications that could have easily shifted the global economic balance. In this section of the paper the authors explore the impact of digital currencies on global trade, examining their potential to cut costs and contribute to economic stability while also addressing the challenges they pose.

Reduction of Trade Costs

The impressive rise of digital currencies has pushed us into a new era of global commerce. With its promise to revolutionize traditional trade practices, potential impacts arose. Digital currencies transformed global commerce by significantly reducing trade costs, making international trade cheaper and more efficient. For example, US exports jumped from $6.45 trillion before the pandemic to $24.9 trillion two years later (Statista, 2023). Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum eliminated the need for banks and payment processors, further lowering the expenses related to cross-border payments and wire transfers.

Faster Transactions

Digital currencies significantly reduced transaction times from days to just minutes, with the number of transactions projected to have increased from 4,000 million in 2022 to over 11,400 million by 2027 (Statista, 2024). This trend benefited the United States and countries like Brazil and China. Mobile banking was a perfect example of faster transactions. Its usage surged by 74% in 2022, leading to a decline in traditional methods like checks and bank waiting times (Federal Reserve, n.d.).

Increased Financial Inclusion

Part of being inclusive was to ensure adults had access to their money. The number of adults without access to any account decreased from 2.5 billion in 2011 to 1.4 billion in 2021. There were also over 2.35 billion registered mobile money accounts worldwide (World Bank, 2022). By offering accessible and affordable methods for transferring value, these digital assets empowered individuals to engage in economic activities. Additionally, they support businesses by increasing financial inclusion and enabling more efficient transactions. This created opportunities for underserved populations, helping to bridge the financial divide and include them in economic participation.

Currency Stability and Hedging

Maintaining currency stability was crucial in the international economy, significantly affecting trade and investments. With the rise of virtual currencies, understanding their role in promoting currency stability has become increasingly important. Currency changes often arose from inflation rates, political instability, or economic downturns. Traditional government-issued currencies quickly lost value, prompting investors and consumers to seek options that preserved value over time. Thanks to their unique structures and controlled supply mechanisms, digital currencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum emerged as potential safeguards against these uncertainties (Chang et al., 2023). Their ability to operate independently from traditional banking systems made them attractive alternatives for managing the risks of fluctuating fiat currency values.

Simplified Exchange Rate Management

The rise of digital currencies noticeably affected exchange rates. Digital currencies, especially CBDCs, became more popular as they influenced exchange rates. This relationship between regular and digital currencies created a complicated situation where financial inclusion and stability were essential (Auer & Claessens, 2020). Digital currencies strengthened financial stability during uncertain economic times. Ozili (2023) highlighted that FinTech innovations, especially digital currencies, helped cushion financial crises. By promoting financial inclusion and reducing costs, these advances stabilized local economies. The introduction of CBCDs gave central banks new tools to address financial instability. Digital currencies enhanced financial stability and reduced volatility during economic crises like those caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. As CBDCs evolved, they shifted trade practices, international relationships, and the global financial system, complicating the balance of power in the economy.

Digital Currencies and Regulatory Challenges

The emergence of digital currencies brought various challenges that required effective regulations. A significant issue was how to regulate decentralized systems that often functioned outside traditional financial oversight (Silva & Mira da Silva, 2022). As the growth of cryptocurrencies sparked debates about distributed governance and the impact on CBDCs. The absence of a centralized authority made enforcement difficult, leading to worries about accountability and compliance in the cryptocurrency space. Additionally, digital currencies created notable challenges for existing monetary policy frameworks.

New Trade Agreements

Digital currencies streamlined cross-border transactions, reduced cost, and improved payment efficiency (International Monetary Fund, 2023). Digital currencies enhanced trade relationships and supported global commerce by facilitating faster and more transparent transactions. Transactions became easier to complete, with clear exchange rates. This motivated both parties to conduct more trade and boosted the global economy. However, challenges such as regulatory issues and the need for clear distinctions between digital currencies arose. Embracing digital currencies transformed international trade, but careful consideration of risks and regulatory frameworks were essential for successful implementation.

Risk of Cybersecurity and Fraud

Cybersecurity and fraud go hand in hand, especially with digital currencies. Cybersecurity refers to protecting these systems from attacks that could leak sensitive information or disrupt services. Fraud was perpetrated via phishing, whereby attackers deceived people into giving up their personal information or money (US Department of the Treasury, 2020). High profile breaches reduced faith in digital currencies, making users uneasy about participating. With these issues in mind, besides hard security measures like two-factor authentication, what was needed was to educate users against the most prevalent frauds. A strong approach to cybersecurity was a challenging but necessary step towards preventing fraud and earning confidence in digital currencies.

Geopolitical Implications

As digital currencies gained ground in the global economy, geopolitical implications arose and affected economies worldwide. One implication was that digital currencies could influence the importance and value of the US dollar. As countries like China developed their digital currency, the digital yuan, and adopted this method for international trade, the Unted States economy faced serious setbacks (Hennessy & Xia, 2024). Some of these setbacks included the erosion of the US dollar’s dominance through shifts in global trade patterns.

Disintermediation

Digital currencies promoted disintermediation in financial transactions. This consisted of removing intermediaries, such as banks and clearing houses, from these transactions in global trade. Through blockchain based transactions, transaction fees and processing times were significantly reduced, leading to more effective and direct payments (Chang et al., 2023). For instance, using CBDCs allowed nations to trade directly in digital assets without going through traditional banks.

CONCLUSION

Digital currencies represent a significant change in the global financial environment, transforming commerce, payment frameworks, and monetary policy. The cryptographic foundation laid by early innovators, along with the emergence of Bitcoin and later the development of altcoins and CBDCs provides evidence of incredible opportunities and significant challenges.

Digital currencies provide singular opportunities to reduce transaction costs, promote financial inclusion, and speed up international trade. The rise of blockchain technology, decentralized finance (DeFi), and the automation of smart contracts have created architectures that enhance efficiency and availability for users worldwide. Most importantly, CBDCs will potentially change financial infrastructures and help solve problems regulating monetary policy and promoting financial inclusion for underserved communities.

On the other hand, there are many obstacles to adopting digital currencies. Regulatory ambiguity, environmental concerns, and privacy threats are some of the risks inherent in these technologies. The speculative nature of cryptos and vulnerabilities in cybersecurity have also cast doubt on their long-term viability. While CBDCs address some of these challenges, they also introduce new concerns related to government overreach and potential erosion of financial privacy. Finally, the role of traditional financial institutions, geopolitical implications, and societal inequities related to access to digital currency also remain open.

As digital currencies are continuously being developed, it becomes imperative that governments, financial institutions, and technological innovators address such intricacies. The harmonious balance required between innovation and regulation has to be reached to maximize the benefits of digital currency while minimizing its associated risk. Thus, the future depends on fostering sustainable ways, inclusive structures, and strong safeguards to ensure that the promise of digital currencies being transformative instruments of the economy is realized globally.

Several countries that previously participated in CBDCs are now inactive: Belize, Curacao, Denmark, Guatemala, Haiti, Iceland, Kuwait, North Korea, St. Maarten, Trinada & Tobago, Uganda, Uruguay, Venezuela, Vietnam, and Zambia.